He found out about it on television, very late. While she was surfing, Delia Cancela saw that a warehouse was on fire in Núñez. Shortly after, she learned that it was the place that kept a large part of the work done throughout her life: from the 1960s in the mythical Di Tella and the designs she made with her husband, Pablo Mesejean, to pieces created shortly before that dramatic January night of 2001. When he arrived at the place, at dawn, he found everything destroyed. "I'm alive, but dead," she then declared to LA NACION, after such a strong shock that she thought she would never recover.

Here it is, though. With her long orange hair, at the age of 80, she goes up and down with agility and a shy smile the long staircase that leads to her house-studio, in Colegiales. He looks the same as when he posed in 2015 in a suit and tie for a campaign for the clothing brand Bolivia, which impacted the mass public with his jovial image from large billboards located on the main avenues of Buenos Aires. Three years later, he won the Grand Prize for Lifetime Achievement, awarded by the National Ministry of Culture, and opened a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires.

“When you get to those two things, in Argentina, you say: 'What else can I do?'”, she now confesses next to her drawing board, surrounded by paintings and a library that includes the catalog of Radical Women, traveling collective exhibition that included his work on its tour of Los Angeles, New York and San Pablo. So, in 2019, she left teaching determined to "travel and enjoy, as you have to enjoy at a certain age."

It was another shock, the pandemic, which for a while left her in a state of creative paralysis and canceled an exhibition she had planned at the Herlitzka + Faria gallery in Buenos Aires. She but she recovered again. She even promoted Nosotras captives, an international project that involves fifty artists from France and Argentina, with the help of her daughter, Celeste Leeuwenburg, and Julia Nowodworski, an Argentine architect living in Paris. "Art is what saves me," admits Delia, as she prepares to return to the French capital after two years without getting on a plane.

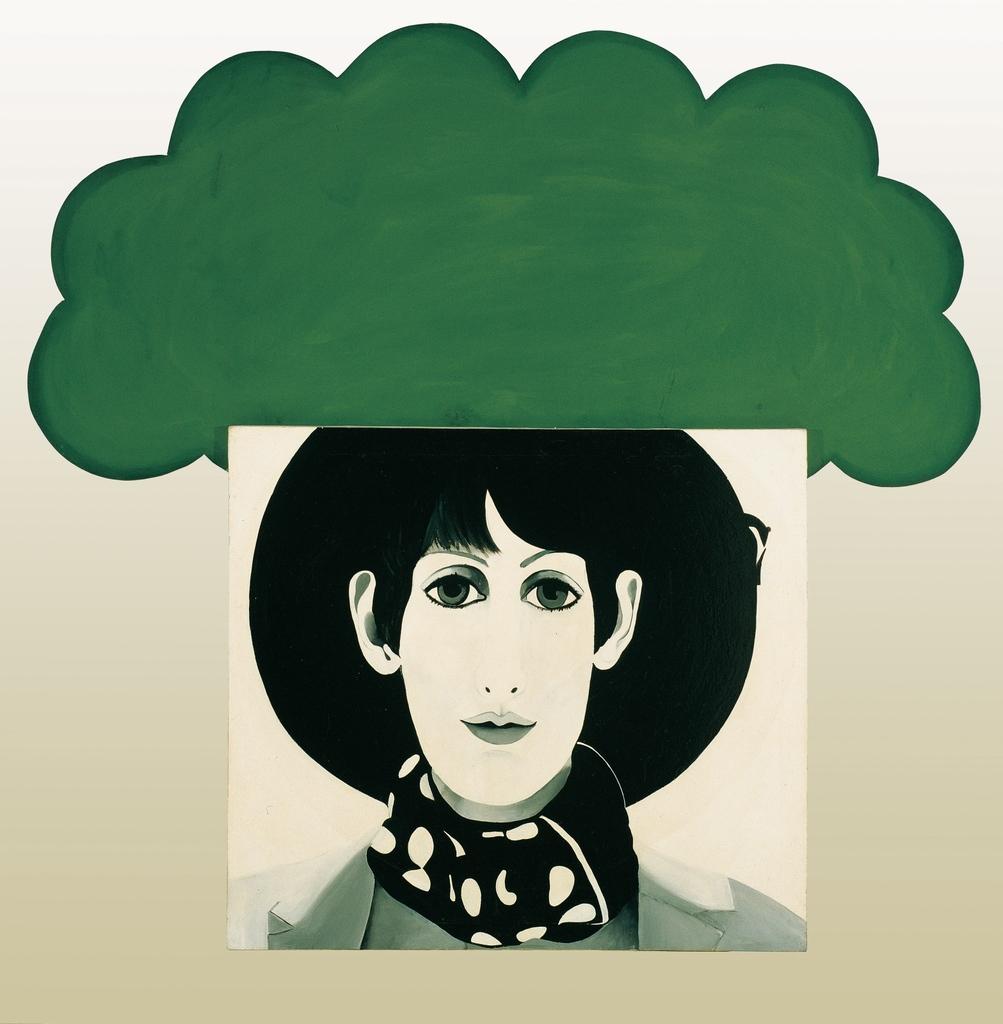

The book El Di Tella, an investigation by Fernando García published this year by Paidós, also put the focus back on that pop era that counted her among its main protagonists. It is recalled there, among other things, that in 1965, the Cancela-Mesejean duo debuted at the Lirolay gallery with the Love & Life: An “acid-free psychedelic” party entered wearing colored-lens glasses, featuring images of flowers, clouds, and astronauts. It was the beginning of an international career that included work for major fashion magazines such as Vogue, Harper's Bazaar and Marie Claire, and the creation in London of his own clothing label, Pablo & Delia, pictured in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

-How have you spent the last year and a half, since the pandemic began?

-Like everyone else: it goes up and down. My life is up and down, I'm used to it. The life of many women is an up and down, because of the things we have to live. I try to take positive things from the pandemic, from all this that we are experiencing. It made me reflect a lot, it made me aware of many things. From the fragility of life, for example. And that it is very important to be attentive. Because this is something that we have been building, which has come in crescendo. And look what is happening now: terrible heat waves, cold, rain, “natural” catastrophes. And the bug, or bugs. I think we have to be aware that this is happening because of how we have lived. If we can become aware and change something, fantastic. If we can't... I'm already big. But precisely, I would like to live calmly and well these years of life, we don't know how many... I'm 80. I say it and I can't believe it.

-Me neither, you look 20 years younger.

-I am an old person who sometimes thinks she is young. Of course I feel it in my body, physically I am not strong... I always felt my fragility, but now I feel it more. At the same time, for me I am still young. And that happens to me because, due to the pandemic more than ever, I look again at my drawings, my paintings, and I realize the need I have to continue doing and researching.

-Did you work a lot on your works during this time of confinement?

-Hard to say. One always talks about productivity. Productivity comes from this system, which is always telling you “you have to do”. And the pandemic tells you: "Can you?" I remember that at the beginning, when the artists were desperate because they couldn't go to the studio, I would say: “That's good, I have a studio in my house”. And he did nothing. Because the shock was very strong. Then the Nosotras captives project was born. I said to myself: "How are we going to communicate, to be able to be close while being so far away?"

-Besides your daughter, you have many friends in Paris, don't you?

-Yes, Paris is a very important part of my life. The links, what I have lived and what I experience every time I am there. If I could, I would try to live half the year in each city. It occurred to me to do as when Celeste was a girl, we played “Exquisite Corpses”: one continued the drawing without knowing what the other had done, based on a clue, and suddenly relationships were discovered in each drawing. I said, "How do we do now?" Because we usually do it together.

-Were the clues sent in images by e-mail?

-Exactly. We began to invite the closest artists. And it grew until it reached almost 50, and they keep adding up. Among others, Edgardo Giménez, David Lamelas, Marta Minujín, Leandro Katz, Teresa Giarcovich, Mariana Sissia, Guillermo Kuitca participated... There are also French artists or those who live in France, such as Marie Orensanz, Antonio Seguí and Pablo Reinoso. Celeste and Julia, who shares a workshop with her, take care of the coordination. It's a lot of work: they receive the photos and print them. They keep the originals of the artists from there, and I keep the ones from here. The French Institute gave us an endorsement and we made a presentation video; Now we need financial help to do an editorial project and a sample.

-You overcame very difficult moments. You raised Celeste alone, and then your works were burned. How did you do it? What did you hold onto to get out of it?

-Ah, you want a life secret!

-Yeah, sure! I wanted to know if art helped you in those moments.

-Art is what saves me. Completely. The do. When I contemplate it, it also helps me. That is why it is so important that museums and galleries are open, because that is not what will lead to the spread of the pandemic. The only way that you can start to think that you can cut it is with a lot of vaccination. I was always against vaccines, but now I say: you have to get vaccinated.

-Why do you think contemplating art saves?

-Because I believe that when you enter a work there is no longer physical time, it doesn't exist. It is like meditation. You're out of your head, which tells you things all the time. Buddhists call it Monkey Mind. The head is always jumping like the little monkey, in that work I'm doing [points to a monkey painted on a canvas]. The fears are there. In the pandemic, the little monkey went off with everything. Art stops that little monkey, and suddenly it locates you. It's the same with books, with music, movies. You enter another dimension. I suppose that with football the same thing happens to many people.

-Do you meditate?

-I deal, every day.

-You once told me that shortly before the fire you couldn't cry anymore. Has that been reversed?

-No. I live without tears.

-But that doesn't mean you don't feel... How are you with that, with having lost a large part of your work?

-That's it. I have a lot of new work: these paintings, the soft sculptures like the apron, a tribute to women artists that I exhibited at the Moderno and at Proa... I did the whole series of soft sculptures with assistants. Now, alone, I can't do big things. I work a lot with little bits that stick together. A fragility... I am interested in experimentation. [Takes up two joined tracing papers] This drawing is one that I had from a work of 1514. And it had this little woman who is sewing her heart together. I pasted it inside that landscape, in which I had already included a chair.

-I think of Corazón destrodado, that work of yours from 1964 that unites the two things: the heart and the pieces hanging. Why has the heart always been so important in your work?

-In the beginning, perhaps as the idea that it represented the female world.

-Did you consider yourself a feminist at that time?

-Yes. I started working without having any idea of what feminism was, because I didn't have much information about what was happening in other countries and there was no one around me who did that. The first works, before the hearts, are collages that have disappeared. There are two photos left, in black and white. At that time, in the early 1960s, I was already a feminist. Those collages talked about the female condition, they had titles like Girls Don't Go Out Alone. For example, there was a collage with a painting by Rubens with those exuberant bodies, and next to it the Miss World receiving the award... Another, with women's and men's clothing: panties, vests, everything that men and women represented. Because I always wondered what was going on, why so much taboo on women. You didn't have to do this, you didn't have to do that... It was difficult. I entered hearts with a slightly more pop idea, when I felt a need for graphic impact, for a single image to speak. Then I start working with Pablo.

-With Pablo they wrote that famous manifesto, Nosotros amamos, for the 1966 Di Tella Award catalogue, in which they anticipated the idea that there are no genders: they said, among other things, that they love “baby-girls, the girl-girls, the boy-girls, the girl-boys and the boy-boys”. What do you think of the progress that has been made in this regard lately? There is also the issue of language...

-Well, let's start with the worst: language. In the language I do not enter. Because at my age, I already have the language that I have. I don't understand.

-Do you think it excludes instead of including?

-For me, yes. I do not think it's necessary. What is necessary is that what is being shown be shown.

-What do you mean when you say “that”?

@TonyGraysome "The butt is on fire" is a Japanese saying. It means "become a cornered situation".

— 超絶偉大無敵テイマー(デジモンワールドデジタルカードアリーナで600勝以上の勝利で得られる称号) Thu Jul 08 14:09:20 +0000 2021

-The difference. We are all human beings. I always thought so, that's why I did those works at the beginning. Because I didn't feel like a woman or a man.

-That's why you also included men's clothing in your works.

-I felt that the most important thing was that I was a human being. The gender didn't matter. Of course, very crazy for that time [laughs]. The same thing happens to me with the woman: if you look at it from the outside you can say: “Okay, enough”. It is true that, now, everything is fine because you are a woman. It's good that it is like that, because at one point that has to exist, so that later it can be leveled. Poor men, in the state they are in, but it is so. The only thing I don't agree with is the language.

-You came to live with two men at the same time. With Pablo, already separated, and with another friend. How was that experience?

-It was great. The three of us lived with Jaime, who was my best friend, like a brother. We lived in a very large house, Haussmannian, on Boulevard Saint Germain. We shared our friendship, each with his room. It was nice. I am a Libra, and sharing is important to me.

-Fernando García's book about Di Tella came out recently... What was it like to relive that era? What was Di Tella for you?

-For me Di Tella was an incredible, unique moment. It was a hotbed of ideas, strength, energy, creativity... That's where things began to be built. I think that a group of artists came together, we didn't even have the same ideas. That's exactly what's interesting. I salvage that part. But the Di Tella was also very noisy. And I couldn't stand the noise. There is also talk that we were very competitive.

-There was even competition between you and Pablo.

-Sure. But it seems to me that competition is healthy… The other day I was talking about it with a friend from Di Tella. Because one thing is competition and another is envy. Don't confuse those things.

-What was there at Di Tella, competition or envy?

-There was envy.

-Was the competition from Di Tella healthy, or not?

-In some people yes, in others no. For example, it is said that there was a lot of competition between the three “top” women of Di Tella, who were Marta Minujín, Dalila Puzzovio and me. Maybe we were competing in how we were dressed, but I think each one of us had a concept of what we were doing, a work that was strong and sustained. How am I going to compete with Marta? Never. I applaud her. The three of us were so different… I rescue what happened to me at that moment, and how that made me able to go out and continue doing. Lots of freedom to do. Which I later took to New York, London and Paris.

-How was the Ropa con riesgo show, with which you presented your first collection at Di Tella, in 1968? Because that was another pioneering work.

-It was a pioneering work.

-You called people from other disciplines as models, right?

-My niece Patricia, who was 11 years old, and Marcia Moretto, who was a dancer, were there. There were models… We did the show in an art institution, something that was not done, where people were sitting and standing, and the models were walking around. They mixed with the public, they moved, they danced… It was a performance.

-And what were the clothes like?

-Despite what they say, that we used plastic things, no... We introduced plastic with Pablo in the 70s, in fashion shows in Paris, where we used large plastic bags as handbags, with bows, accessories that were cut out in plastic… But at Di Tella they were painted cotton, silk. It was a risk to wear those clothes in Buenos Aires, in Argentina it was a scandal. But it didn't seem like a scandal to me. We were obviously breaking with something, because when we came to London and showed our work, Vogue immediately opened the doors for us. And they considered us artists who worked in fashion.

-And already in New York it had happened to them too.

-Yes. But we did it very naturally.

-Did you ever consider yourself a hippie? I know you don't like labels, but...

-And you put them on me! [laughs]. A fancy hippie. I remember that we arrived in New York, with the clothes that we wore with Pablo from Buenos Aires, and the groovies and hippies stopped us in the street and told us that we were great.

-What did they wear, for example?

-I had cut my hair very short and I left some long strands of hair that hung down, like the orthodox. We used very wide dresses, with some old fabrics, with jeans below and shoes with heels, which we painted by hand. The look we had was important.

-And Paul?

-Pablo was very mod… We dressed very English. That was interesting: the United States was looked at a lot here, in terms of the look as well. While Pablo and I looked at Europe.

-And where did they get that from?

-First, from our first trip, in 1967, when we went to Paris on scholarships with the Braque Prize.

-Is it true that the prize contemplated a single ticket, and he went by plane and you by boat?

-Yes.

-Is that because of your fear of flying or…

-[Laughs] Because men had to do that. Juan Stoppani and Pablo flew out and waited for us in London, and with Alfredo Arias we arrived in London by boat.

-Something macho, let's say.

-What do you think? Our duo Pablo and Delia, or Cancela-Mesejean or Mesejean-Cancela comes from the competition. Of the clashes about whether they invited me and they didn't invite Pablo. There is one thing that is very interesting at that time: that women had a place at Di Tella. They were inviting me to many places, I was doing very well. And Pablo too, by his side. But Pablo couldn't stand it. So I told him: let's work together.

-You say that from that first trip you already began to see what was happening in Europe... Or did this innovative look of yours come from before?

-It came from us. What we did was accepted in Europe, and in the United States as well. We were contributing.

-Did you dress in men's clothes too?

-Yes, I had a suit that I had made here by a tailor, black. Jacket, pants and vest. And he wore a shirt.

-Did you ever like women?

-I love women, I love them, I get along very well with women.

-Like to have a partner, I mean.

-No, I prefer boys. At this point in my life it's hard to say so, but… My attraction has always been the legs of soccer players. Love has nothing to do with sex, right?

-What is the message of all your work, right?

-Yes.

-What are you working on right now?

-Many drawings. In 2020 he had planned a solo show at Herlitzka + Faria. It was postponed, like many, to 2021. And this year it was not done either. I was preparing something that I had been doing for a long time, about the relationship of women with nature. It was shown on the Vortic platform, in England, with a virtual gallery called Southern Stars.

-Like that work you have in the back?

-Of course, they are previous works. Nature is very important and the woman is there, in the middle. The geometry represents the urban, what is being destroyed… It is from 2015.

-How premonitory. Because now with the pandemic there is this exodus from the urban to nature.

-Yes. In that other one, nature is also destroyed, and the woman in the middle, very strong...

-Like empowered. Do you like that word?

-Yes. As if empowered in the middle of that sky, that green… They are like pieces. It is also from 2015, when he could still do big works.

-And man has no place in those works.

-No. It has had its place for a long time. Now it's the woman's turn. I believe that women are more conscious than men in their relationship with nature.

-Which is what we were talking about at the beginning. You said that the pandemic led us to be more aware.

-Yes. It seems to me that the woman is more aware of what is happening.

-For a reason it is said that it is “Mother Nature”.

-Exactly, the Pacha Mama.

-You always say that you feel identified with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, your bedside book. What attracts you so much to that character?

-I started reading Alice as a child, with the Robin Hood books. My dad used to buy me the whole collection. They were my first readings.

-Also the magazines he distributed, like Burda, right?

-Also. And I felt identified with Alicia, still sometimes I feel identified. Because that girl has to accept the rules that society imposes on her, she has no other choice, and she rebels. He wonders why, he is always questioning. And at the same time he passes through the mirror, eats the mushrooms...

-In other words, it accepts the rules, but seeks to transform them.

-Total transgressor. But she's still the careful girl. That's why, when you ask me if I was a hippie… I lived that moment. But he had no need to live in destroyed houses. It doesn't matter if I didn't want to do that. Taking drugs… Yes, I took drugs, of course. But in another way.

-So you did what Alice did: you took what was there, you adapted, but at the same time you transformed.

-I got lost too. Those were very crazy times, especially Paris. These are times of great madness because they are times of many changes. AIDS was also important, it was brutal. Of much pain, of many losses. They have compared it to this moment, but it is not the same. One could stop doing things so as not to get infected, take precautions. This is global, it is something else. The only thing that makes me angry is that I mentally prepared myself to enjoy these coming years. I no longer had to worry financially, I could work, do whatever I wanted... But when I think about what people who have nothing, who are on the street, are experiencing, I say: "Delia, shut your mouth."